Concept of the fortnight: alloparenting

There's a reason why 'it takes a village' is a cliché...

This week I’m testing out an idea for a new regular segment: ‘concept of the fortnight’. This will be a shorter post where I share a concept that I find interesting, fun or useful.

I decided to this because I’m a sucker for a good concept and I figured I can’t be the only one! A nice, juicy concept can help us understand the world, make sense of the predicaments we find ourselves in, and possibly help us find a way out.

Also, frankly, I’m tired. Juggling raising a two-year-old with work and bureaucracy while having a chronic illness and trying to live in two countries can have a way of wearing you out. As much as I love writing and sharing them, I just don’t have capacity for a full essay-type post every week, so I’m trying out alternating those essay-type ones with these shorter, simpler ones.

‘Why don’t you just publish less frequently?’ You may well ask, as my husband regularly does. Because a) I like the ongoing contact with my writing and my readers, b) I’m worried that the algorithm will forget I exist and c) I’ve got hold of this ‘concept of the fortnight’ idea now and I’ll be damned if I’m letting go.

The concept: alloparenting

For all the reasons above, I chose alloparenting as our first concept. Alloparenting is a term from anthropology to describe the practice within certain species of members caring and provisioning for offspring that aren’t biologically their own.

I actually first heard of this term from an email exchange with Cat Bohannon, who wrote the 2023 book Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution. I’d written a post on the concept of ‘eusociality’ which I’d discovered from that book, and shared the post with Cat, who wrote back and told me about alloparenting.

Homo sapiens are a species of alloparenting. We help raise our grandchildren, our nephews and nieces, we adopt children who aren’t genetically our own, and we help our friends with their kids (sometimes, circumstances permitting, even in a genuinely meaningful way, beyond holding them once as a newborn until they sick up on your dress and then pretending not to mind when your friend brings them to your brunch catch-up).

Humans aren’t the only alloparenters. According to the anthropologist Sarah Hrdy, the phenomenon occurs in 9% of living species of birds and around 3% of mammals. Our fellow alloparenters include Costa Rican Magpies, whose allomothers often bring more food to fledglings than their own mothers do, as well as marmosets and tamarins. In this sense, we humans share more with these tiny-brained monkeys than with the four great apes, whose mothers care for their infants alone.

Hrdy believes that alloparenting is part of our deep evolutionary history, tracing it back to the Pleistocene epoch beginning 1.8 million years ago. Hrdy thinks that modern humans’ big brains and our extraordinary capacity for intersubjectivity — our skill of tuning into and sharing the emotional states of others — developed thanks to our alloparenting and collective breeding practices.

Why should we care?

I refer to you to my prior comments about being knackered. Getting beyond the confines of the nuclear family is constant yearning for me — as I’m sure it is for many of you. I love concepts that confirm what is already obvious: that we are not supposed to be raising children in tiny, isolated units. The idea of alloparenting gives this intuition grounding in our deep history and can fortify us on our quests to overcome this silly nuclear setup.

‘Nobody has ever before asked the nuclear family to live all by itself in a box the way we do. With no relatives, no support, we’ve put it in an impossible situation,’ wrote the famous anthropologist Margaret Mead.

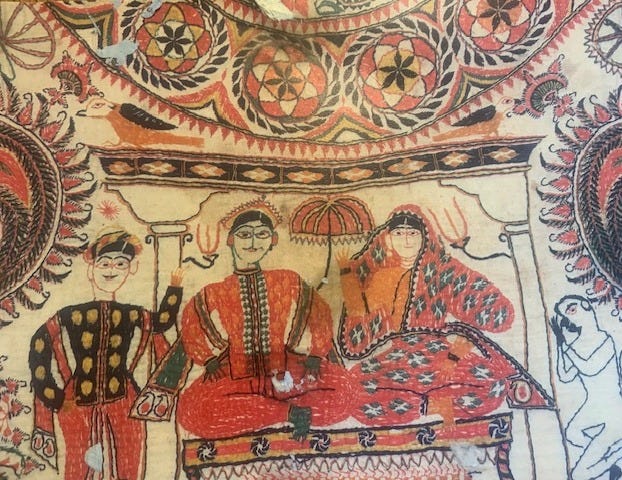

Mead thought it was preferable for children to be raised in a network of caring people, to be part of multiple households, as she had encountered in her studies in Bali, New Guinea, and Samoa. She advocated for ‘cluster’ units comprised of older married couples, child-free people, and teenagers from other households. Mead raised her own child this way, which also freed her to travel and work away from home.

As my husband, Erik, and I have found, actually making this happen is, let’s say ‘challenging’, when you have been brought up in the type of capitalist society that favours the nuclear arrangement (most economically ‘advanced’ countries).

The most drastic thing that Erik and I are doing in pursuit of this dream is spending large chunks of time in London, where my parents live. For the past two years, we’ve uprooted our lives twice a year and dragged our unit-of-three back and forth between London and Nijmegen, where Erik is from.

While we’re in London, our celestial ‘allomother’ (my mum) takes care of Essie twice a week. Essie feels right at home in my parents’ house, my dad spends all day cooking for her, and she loves nothing more than when we all go away for a few days and stay together in a holiday home (though this invariably results in at least one nervous breakdown on my part — no-one said alloparenting would be trauma-free).

While we’re in Nijmegen, Essie is lucky enough to have two partial alloparents. Our friend Crystal takes her once a week, and she goes to our friends Louise and Poe on Saturday mornings and plays with their two older boys, all of which she adores. Erik’s dad and his partner are also an important part of her life.

All of our alloparents tell us that caring for Essie means a lot to them too. Thankfully, mutual reward seems to be part of the whole alloparenting design, though of course we always need to tread the line of not taking the piss.

None of this has been a walk in the park. We’ve built this fledgling community gradually over a period of years, and it’s still only gotten us partially beyond the nuclear situation. It costs a lot of money, it’s a bureaucratic migraine, heaven knows what we’ll do when Essie reaches school-age — and then there’s those god forsaken borders.

We are in the relatively ‘privileged’ position of being able to cobble our lives together in this way, at least for now. Most people wouldn’t be able to do this because our societies and global economy are structured to get in the way.

But at least the concept of alloparenting and the idea of ‘clusters’ of people of various ages and life configurations raising children together can give us a kind of compass — a light to guide us as we bump along our parenting paths.

Leave a comment! I’d love to hear from you:

What are your wishes and values when it comes to family life and balance?

Have you managed to form a family structure that goes against the grain of your society? How??

Are you an alloparent or would you like to be one?

Anything else you’d like to share!

Thanks for writing this despite recent exhaustion, I feel you!

I first heard about alloparenting via Tracey Cassels https://evolutionaryparenting.com/when-being-a-primate-makes-parenting-so-much-harder/

It’s so easy to feel defeated as a parent working a job, doing ALL the things and raising children with minimal support but I appreciate Tracey’s idea of “evolutionary mismatch”.

We can be kinder to ourselves when we remember we’re primates - living in a nuclear unit that doesn’t match up with what our children (and the part of us that’s not solely ‘mum’) actually need to thrive.

“I forgot to mention I believe I experienced alloparenting firsthand. My mother and father were very young when I was born, so the care and guidance of my great-mother, grandmother, aunties, uncles, even my older sister, and the wider community all helped shape the rhythm and texture of my early life. It was truly a shared weaving of my childhood.”