Are humans inherently evil destroyers?

It's our social systems, not our nature, that are to blame. It's time we tell new stories about what it means to be human

Last week I had maybe the best haircut I’ve ever had. The young hairdresser had a preternaturally gentle vibe and instantly put me at ease. We chatted comfortably about our shared mixed race heritage and the various ways in which we were products of colonialism. She gave me excellent hair advice and, I don’t want to jinx it, but I think I’m about as happy as I’m ever going to be with the result.

Of course, we also talked about the weather, which was predictably dreary. She said she likes to think of the weather as having feelings. I told her that my two-year-old had remarked that morning that the sky was crying just like she was crying. My hairdresser said that, given the climate apocalypse, she doesn’t think that people really have the right to complain about the extreme weather that we so often get these days, since ‘it’s definitely our fault. We probably should have done something about that earlier.’

I didn’t say anything, but I wondered who she was including in the ‘we’ she invoked. Whose fault exactly is the climate crisis? Humans in general? British humans? Humans alive today?

If she meant humans in general, she’d have been repeating a very common narrative that humans as a species have destroyed the world. This thinking often comes with the assumption that our species is innately invasive and destructive. By extension, the implication is that we therefore deserve the suffering and potential extinction that we face.

But how true is this? Before anyone accuses me of climate denial, there’s no doubt that humans are poisoning and killing the world. But is this all humans? Is there something inherent to humans that make us so destructive?

Who is this ‘we’?

Actually, a scientific study published in May 2025 found that the world’s wealthiest 10% have contributed two-thirds of global warming since the 1990s.

One of the authors, Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, said that if everyone had emitted the same amount as the bottom 50% of the global population, there would have been minimal additional warming.

Strikingly, both the causes and effects of global warming follow the contours of colonialism. The regions that have contributed the least to climate change — including the Amazon, Southeast Asia, and southern Africa — are all facing the most devastation from its effects. These regions also have the fewest means to combat it.

Another study found that Indigenous peoples, while comprising less than 5% of the world’s population, protect 80% of global biodiversity. So it’s not all humans that are at fault.

I’m not blaming my lovely hairdresser for this, but the narrative that humans are inherently a destructive species who deserve the cosmic karma of annihilation, glosses over massive fault-lines of class and race within the human population.

In fact, the idea that humans are destined to dominate other species is part of the same ideology that created those fault-lines within humanity in the first place. Let me explain.

Zoological racism

The idea that humans are a species doomed to be evil, is a kind of pessimistic mirror image to the triumphant humanism of the Enlightenment. In that view, humans were fated to be the ‘masters’ of the natural world, created to bend nature to our iron will.

This ideology complemented the rise of a new global economic order, capitalism, from around the 16th century. Capitalist industrialisation saw unprecedented human domination over nature — its mines ripping open the land, its factories spewing out toxins, its steely monsters chewing up forests.

This view of humans posited a fundamental separation between humans and the rest of nature. Not just a separation, it created a hierarchy, whereby humans were inherently superior to all other species. This justified unfathomable environmental destruction. CO2 emissions have increased by over 40% since the start of the industrial revolution.

It didn’t end there, however. The thing with hierarchies is, they have a habit of multiplying. Think of hierarchies, if you will, as ‘fractals of doom’.

Upon this one giant hierarchy between ‘humans’ and ‘nature’, capitalism’s emerging elite built a whole series of hierarchies within humanity. These were hierarchies of coloniser and colonised, men and women, rich and poor, able-bodied and disabled, cisgendered heterosexual and ‘deviant’ genders and sexualities.

All of these hierarchies were fundamental to capitalism, just like the stomping of nature was. Seeing some humans as inherently inferior to others justified wholesale domination and plunder. Where do you think those lovely profits that drove the industrial revolution came from?

And all these hierarchies feed into each other. Claire Jean Kim shows that racism is zoological in nature – it works by reducing Black people to the status of animals. Just think about the monkey chanting at football matches. But that dehumanisation can only work if other animals themselves are seen as without intrinsic worth in the first place, and therefore open to the most horrendous treatment.

(Btw, if, like me, taking your kids to the zoo makes you feel weird, there’s a reason for that…)

Since the 1970s, ecofeminists have similarly seen the oppression of non-human nature, women and colonised peoples as part of one and the same project. The sixteenth-century scientist Francis Bacon, for example, referred to nature as a woman who needed to be forcibly penetrated by ‘scientific man’ to discover her secrets.

All of these violent hierarchies are structurally linked through capitalism and its obsession with profit. If we want all humans to be recognised as fully human, we need to get rid of that underlying hierarchy between humans and the rest of nature.

On being humon (yes I am a closet Star Trek nerd)

From the early nineteenth century, this idea of humans as ‘man the dominator’ span off into another conception of humanity: homo economicus. Developing alongside capitalism and becoming more widespread during the ‘neoliberal’ era of capitalism since the 1980s, this notion of humans reduces us to ‘economic man’, driven by self-interest and rationality to maximize his own well-being.

This concept of humanity is very convenient for those who want to colonise Mars and upload their brains into internet clouds, but it’s not so handy for those of us who are all-too-aware of ourselves as soft animals who really just want to cuddle.

The rise of homo economicus has accompanied a period of unprecedented destruction: since the 1980s, global warming has occurred at three times the rate of the previous period (which was already super destructive).

It isn’t our nature but our social systems — especially capitalism — that has led to some of us inflicting unimaginable violence on others. If humans do have an innate ‘nature’, it’s probably that we have both violent and intensely loving sides, and a lot more in between. We can choose whether we create systems that feed one side or the other.

We can decide to be neither ‘man the dominator’ nor homo economicus, but instead live in peace both with our fellow humans and with our beyond-human siblings.

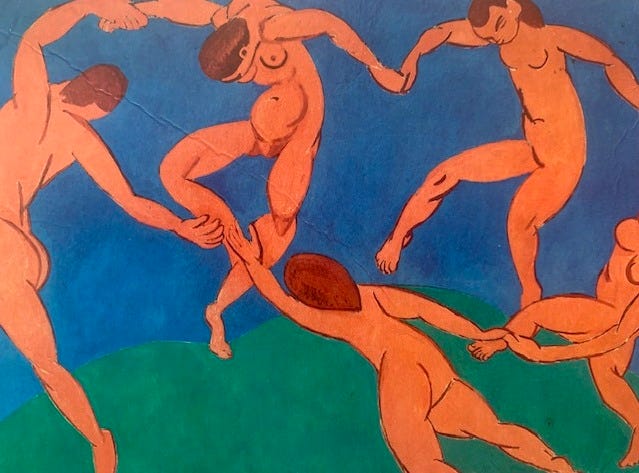

The poet and scholar Sylvia Wynter wrote that the one thing that distinguishes humans from other animals is that we are a species of storytellers. We can trace our capacity for storytelling to the Blombos Cave in South Africa, where the first cave drawing was found, dating back 73,000 years.

If I could have that conversation with my gentle hairdresser again, I’d say that I hope we can reclaim this part of ourselves to tell a new story about what it means to be human — one in which we all live happily ever after.

*My brill hairdresser has given me permission to tell you that her name is Mya and the salon is Shorties in Clapton, London (and no I’m not getting any commission!)

My driving instructor coached me through my first turns by saying: “you have to look at where you want to go, that way you will automatically steer in the right direction.” It feels like all lamenting on human being as evil doers is doing exactly that. It paralyses our good instincts. Social media and public chatter is inundated with this “oh we people are awful”. But we are also a species that take pleasure in forest walks, having communal meals, we start elephant sanctuaries and we think of ways to alleviate suffering of other all the time. Eyes on the road people, where do we want to go?

All this to echo the very point you are making! Loved this essay.

Love this essay and I totally agree! I also think that this negative idea of humanity gives a justification for when we know that something isn’t right but want to give in to the ‘lazier’, more selfish, less kind path because in the moment it’s easier. It takes effort to build community, make responsible choices for the planet, and work on our own prejudices and areas of ignorance, and we’re constantly being encouraged by capitalism and divisive, individualistic politics to just not bother.

There are so many genuine reasons that people don’t have capacity for this, so I’m really trying to hold myself to account as someone who does - and it makes life so much better! I find that surrounding myself with people who inspire me to do better (IRL through community groups and in those whose work I follow), rather than consumerist content that encourages my most selfish impulses, really makes it easier to push myself bc it makes the ‘norm’ a higher standard.