AI is writing poetry while I clean up toddler poop

From ‘microworkers’ to ‘global care chains’, there are millions of exploited workers behind our high-tech economy

I recently went to an exhibition titled ‘We Work Like Peasants While AI is Out There Painting and Writing Poetry’. It was the first time that I had gone to see art by myself since my daughter Esmeralda was born two years ago. I take her to lots of museums but that mostly involves trying to stop her from tripping over things and her chatting to the various abstract women’s faces and blobby sculptures while forcing me to impersonate funny voices for them.

Going by myself was glorious. It was a beautiful Spring day, the blossom was blooming, and I relished exploring the formerly squatted complex in Nijmegen that housed the DIY art space. I had to pay €2.50 to get in which, petty as I am, I resented. But I’m glad I did have to pay that nominal fee because, petty as I am, it made me invest that bit more in engaging with the work.

I was the only one there and it was a pretty casual affair. There was one video installation that didn’t have the sound turned on and had no chairs in front of it to sit on (maybe the hipster youths in charge didn’t have the energy levels of a forty-something chronically anaemic mum in mind when installing the exhibition). Usually I would have just skipped that exhibit but this time I asked the person working there if she could turn the sound on and, like Will Smith in Men in Black, I noisily dragged over a chair from another part of the room so I could sit down and really absorb the piece.

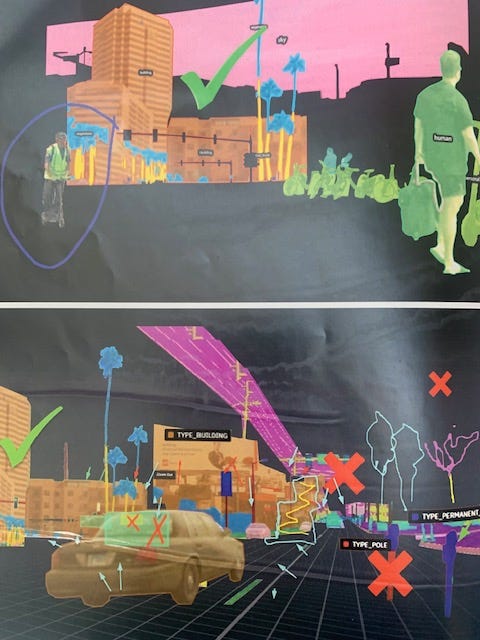

I’m glad I did. It was about the ‘microworkers’ who train the machines that control self driving cars. These are mostly workers from the Global South – including from Kenya, Venezuela and the Philippines – who get paid maybe $1.50 an hour to complete thousands of minute, fiddly tasks that stop self driving vehicles from stampeding over Silicon Valley dwellers and splattering their Bermuda shorts all over the sidewalk.

According to the journalist Adele Walton in an article for

, there are around 20 million people doing the microwork that makes intelligence intelligent.The installation displayed abstract renditions of the work these labourers perform on their screens – their cursors tracing with intricate precision around every single object in a frame depicting a Californian street scene, and labelling or querying each object.

On the audio track you hear their voices speaking about their work. They talk about how they imagine the places that they are so intimately portraying, with their wide streets, urban planning and white people. They share how they apply their creativity to the monotonous tasks, and how engaging with the world in this way alters their perception. They reveal how they tried to hack the system using VPNs when they discovered that microworkers in the US get paid $2 a task while in Venezuela it’s 20 cents – and how they were thwarted when the company spied on them in the group app.

The piece ends with a Kenyan worker reflecting on how this kind of automation might not work so well in Nairobi because “Nairobi drivers don’t obey the rules” – and neither do the large herds of cattle (“maybe more than even a hundred cows”) who share the roads.

It dawned on me that the automated economy is a big fat lie. It takes vast armies of massively exploited workers to automate things. This economy follows the fault lines of neocolonialism. In place of the overt colonial occupations that mostly ended after the Second World War, today’s neocolonialism works in large part through what the acclaimed economist Samir Amin called ‘unequal exchange’. This means that rich countries and corporations use the wealth and power they stole during old school colonialism to force wages down in the rest of the world. They do this across all sectors of the economy, so it’s really no surprise that neocolonial exploitation underlies a lot of automation.

Given my current life, this made me think of another vast army that gets paid nothing at all but without whom capitalism – life itself, in fact – would grind to a halt. That would be mamas, and all those who take care of children and other people who need caring for.

In a previous post, I wrote about the ecofeminist Maria Mies and her book from the 1980s, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale. There’s one part of the book that made me giggle, reading it from the vantage point of forty years after it was written. She wrote that many women would recoil in horror at the idea of reducing the time spent at work through automation. This is because we know full well that what automation would mean in practice was more work for us, assuming that raising children and supporting relationships would not be automated. The day in the factory, office or industrialised farm might be shorter but would that mean less work for those taking care of the babies? I don’t think so, my friend, not under our current socioeconomic system.

My partner Erik and I are permanently exhausted, as are basically all parents, as far as I can tell. “I need a holiday” Erik occasionally says, “let’s go away”. I recoil in horror. “A holiday from what??” Presumably Essie would be coming with us on this holiday? How is that less work? The fact is that doing our paid jobs – which for Erik and me means sitting in front of our computers – is a relaxing rest compared to the relentless work of parenting.

I’m not really sure how automation could solve this. Perhaps there are some aspects of parenting that could be automated, but most of it involves actively attuning to the child, which is necessary for their development. In our household, even changing nappies involves quite a lot of chatter and make believe, which feels like more than a nice-to-have for Essie’s fizzing brain.

In any case, even if parenting could be automated, going back to microworkers, the whole point is that automation isn’t really automated at all, it involves a lot of neocolonial uber-exploitation.

Actually, even without automation, care work already also follows neocolonial lines. Although the majority of care work – like parenting and taking care of elderly relatives – is not remunerated at all, much of it is part of the paid economy. Think daycare centres, nannies and carers. This work is outrageously underpaid, given how vital it is to our wellbeing and actual lives. It’s often done by immigrant workers, usually women, perhaps from the Philippines, Jamaica, Guatemala, India or Botswana.

These women are often mamas themselves. Who is looking after their babies? Often another female relative, perhaps a sister or daughter. What opportunities are they losing by having to do this? The sociologist Arlie Hochschild refers to this dynamic as ‘global care chains’, the outsourcing of middle class people’s care work.

Whether it’s grotesquely underpaid or not paid at all, who is all this labour ultimately benefitting? Spoiler alert, it ain’t us. At least if we’re tending to our own kids then that’s (hopefully) its own reward, though we get so little support that it’s hard to appreciate that sometimes. But even so, we’re all plugged into an economic system that is designed to chug wealth to those at the top by draining the rest of us.

We’re all serving that system with the work we do, even if we don’t intend to and even if we think we’re doing it purely out of a gushing fountain of love. If we want institutions like work, social care and the family to genuinely serve us, we are going to have to build an entirely new economic system centred not on profit but on care and love.

Ooh I know, how about mums, microworkers and carers gang up with AI to lead a rag tag rebellion and topple our capitalist overlords? I’m pretty sure AI is writing that story while I clean up toddler poop.

reminds me of metropolis.